Unemployment and Substance Use a Review of the Literature (1990-2010)

- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

Unemployment charge per unit, opioids misuse and other substance abuse: quasi-experimental evidence from handling admissions data

BMC Psychiatry volume 21, Article number:22 (2021) Cite this article

Abstruse

Groundwork

The human relationship between economical conditions and substance abuse is unclear, with few studies reporting drug-specific substance corruption. The present study examined the association between economic conditions and drug-specific substance abuse admissions.

Methods

Country almanac administrative data were drawn from the 1993–2016 Handling Episode Data Gear up. The event variable was state-level amass number of treatment admissions for half-dozen categories of primary substance abuse (alcohol, marijuana/hashish, opiates, cocaine, stimulants, and other drugs). Additionally, we used a broader outcome for the number of treatment admissions, including master, secondary, and tertiary diagnoses. We used a quasi-experimental approach -difference-in-deviation model- to approximate the association between changes in economical conditions and substance abuse handling admissions, adjusting for country characteristics. In addition, nosotros performed ii additional analyses to investigate (1) whether economical weather take an asymmetric effect on the number of substance utilise admissions during economic downturns and upturns, and (2) the moderation effects of economical recessions (2001, 2008–09) on the relationship between economical conditions and substance utilise treatment.

Results

The baseline model showed that unemployment charge per unit was significantly associated with substance abuse treatment admissions. A unit of measurement increase in state unemployment rate was associated with a 9% increase in handling admissions for opiates (β = 0.087, p < .001). Similar results were establish for other substance abuse treatment admissions (cocaine (β = 0.081, p < .001), booze (β = 0.050, p < .001), marijuana (β = 0.036, p < .01), and other drugs (β = 0.095, p < .001). Unemployment rate was negatively associated with treatment admissions for stimulants (β = − 0.081, p < .001). The relationship between unemployment charge per unit and opioids treatment admissions was not statistically significant in models that adjusted for country stock-still effects and allowed for a land- unique time tendency. We institute that the association between country unemployment rates and annual substance abuse admissions has the same management during economical downturns and upturns. During the economical recession, the negative clan between unemployment rate and treatment admissions for stimulants was weakened.

Decision

These findings advise that economic hardship may take increased substance abuse. Treatment for substance apply of certain drugs and booze should remain a priority fifty-fifty during economic downturns.

Background

Substance abuse, the harmful or hazardous use of psychoactive substances, remains a significant public health problem. In 2017, approximately 74,000 persons died of drug-related causes, and nearly 36,000 died of alcohol-related causes (excluding accidents, homicides, and prenatal exposure) [one]. The U.s. has experienced an increase in the prevalence of illicit drug utilise, from 8.3% in 2002 to 11.2% in 2017 [two, 3]. There has also been a recent rise in the use of marijuana from 14.5 million (five.8%) in 2007 to about 41 million (15%) in 2017 [ii, iii]. In dissimilarity, alcohol dependence decreased from 18.1 one thousand thousand (seven.7%) in 2002 to 17.three million (6.6%) in 2013 [2]. In 2017, virtually 17 million persons (6.i%) reported heavy booze use in the past calendar month, and nearly 67 million (24.5%) reported binge booze use, a slight increase from 2016 [2].

The relationship between economical weather condition and substance corruption is ambiguous. Several studies have found that tighter budgets during economic crises impacted drinking behaviors, including less alcohol consumption, with people switching to cheaper products and drinking at domicile rather than drinking at bars [iv,five,6,seven]. However, prior studies have documented that economic downturns, along with their related stresses such equally job loss, are associated with increased problematic drinking [eight, nine]. There is besides evidence that unemployment is strongly associated with problematic substances use, including the use of booze, marijuana, and illicit drugs [10]. An international study from Australia found that economical downturns were significantly associated with the frequency of marijuana use amidst immature adults, and a procyclical relationship was establish for the frequency of drinking [5]. Furthermore, multiple studies have constitute that sales and use of marijuana and other illicit drugs increased amongst young adults and teenagers as the unemployment rate decreased [11, 12]. A study conducted among African American adults in Milwaukee's inner metropolis found that those employed full-time tested positive for cocaine less often than those who were unemployed, and those employed role-time had higher rates of testing positive than those employed full-time [13].

Substance abuse treatment admissions can exist used as an indicator of excessive or problematic substance use. Yet, due to a lack of bachelor quality drug abuse and treatment data, existing research has been limited to investigating general substance apply treatment admissions (non drug-specific) or restricted to certain subpopulations. In add-on, few studies accept examined the association betwixt national economic conditions and substance use [five, 11, 12, 14].

A contempo study in the U.S. based on cocky-reported information establish that economic downturns led to increases in the intensity of prescription hurting reliever use also as opioid substance apply disorders, particularly among working-age white males with low education [fifteen]. The present study expands on prior work, examining the relationship between economical conditions and substance employ, using admissions data from the 1993 to 2016 Treatment Episode Data Sets (TEDS) and a more than diverse fix of illicit drug categories (i.due east., alcohol, marijuana, opioids, stimulants, cocaine) [16].

Methods

Information

TEDS is a national access-based data system administrated by the Centre for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality of the Substance Corruption and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Since 1992, the TEDS system has compiled data from each state to track annual discharges and admissions to public and private substance abuse facilities that receive public funding. Treatment facilities that receive public funds or are licensed or certified by state substance abuse agencies are required to report data on all clients, regardless of health insurance status. The TEDS system comprises two major components: the Admissions Information Set up and the Linked Discharge Data Fix. Both data sets provide demographic, clinical, substance service characteristics and settings, employment status, presence of psychiatric bug, prior history, route of administration, insurance status, and source of payment for all patients 12 years of historic period and older. In addition, 3 (primary, secondary, and tertiary) substances of corruption, their road of administration, frequency of use, age at first apply, and a source of referral to handling are recorded for each admission. TEDS classifies substance use into vii categories: alcohol, marijuana/hashish, opiates (heroin, non-prescription methadone, and other opiates and synthetics), cocaine, stimulants (methamphetamine, other amphetamines, and other stimulants), other drugs, and none reported. We used the TEDS admissions data set from 1993 to 2016, excluding the "none reported" category.

Measurement

Dependent variables

Country identifiers in TEDS were used to derive the land-level aggregate number of handling admissions for six categories of primary substance utilize (booze, marjuana/hashish, opiates, cocaine, stimulants and other drugs) for each year individually. Additionally, we used a broader effect for the state-level aggregated number of treatment admissions, including primary, secondary, and tertiary diagnosis for any each category of substance use.

Independent variables

Our primary dependent variable was economic condition. Nosotros used land unemployment rates to represent the economic condition. State unemployment rates and median household income (in chiliad dollars) for each state were obtained from the Bureau of Labor Statistics [17,18,19]. Nosotros also obtained country laws on medical marijuana laws fromProCon.org [20], land alcohol taxes from the tax policy center [21], and the insurance coverage rate for each state from the U.S. Census Bureau [22]. We followed the Demography Agency'due south recommendations for obtaining insurance coverage rates and used the Wellness Insurance Historical Tables - Original Series for 1993 through 1998, the Electric current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS ASEC) information to estimate 1999 through 2007, and the American Community Survey (ACS) for rates subsequently 2007. These two estimates differ slightly only parallel in modify betwixt 2009 and 2012. Additional country-level characteristics including the log of population, mean age, percentage of the land population that is male, and percentage of the population that is white were calculated using U.S. Population Data through the National Cancer Establish (NCI) [23]. The aggrandizement-adjusted beer excise tax was measured in each state at the 2018 price level.

We created a dichotomous indicator, economic trend, to test whether economic weather had an asymmetric issue on substance use treatment admissions in economic upturns and downturns. When unemployment was higher than in the previous period, the economy experienced a downwardly trend. Otherwise, the economy was nether expansion. We additionally created a recession indicator. The two periods, 2001 and 2008–2009, were considered recessions with negative economic growth, in accord with the National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc assessment [24].

Statistical analysis

Nosotros used difference-in-difference (DID) models to estimate whether changes in economic conditions were associated with changes in substance use treatment admission. Generally, DID is a quasi-experimental design used to estimate the result of a specific policy or intervention (country unemployment rate in our study) by comparing the changes in outcomes over time between the handling group and control group [25]. The outcome variable, the state-level amass number of treatment admissions, was log-transformed in society to address potential skewness. Multivariable linear regressions models were used to assess the association betwixt the economic condition (state unemployment rate) and substance employ treatment admissions. Model one adjusted all listed state-level characteristics, including log of population, hateful historic period, pct of state population that is male, percentage of country population that is white, state insurance coverage rate, land median household income (in thousands), medical marijuana laws, and survey year. Model one additionally adjusted for demography segmentation fixed effects to capture unobserved confounders that cluster among neighboring states at the division level. State beer taxes were adjusted for booze substance use handling only (see eq. (one)).

$$ {Y}_{st}\sim {\beta}_1\ast Eco{n}_s+{\beta}_2\ast {Year}_t+{\beta}_3\ast {Division}_s+\sum {\beta}_j{X}_{st}+{\epsilon}_{st} $$

(ane)

Model 2 adapted for state fixed effects to command unobserved confounding influences that are time-invariant and state-specific. We used variance aggrandizement factors (VIF) to check for multicollinearity in covariance betwixt the included state-level characteristics and country fixed furnishings. We elected not to include the log of population and percent of the state population that is white in Model 2 (VIF > 10) (see eq. (ii)).

$$ {Y}_{st}\sim {\beta}_1\ast Eco{north}_s+{\beta}_2\ast {Year}_t+{\beta}_3\ast {State}_s+\sum {\beta}_j{X}_{st}+{\epsilon}_{st} $$

(two)

Model 3 added interaction between state and year to Model 2, in order to let for a country-unique time tendency and control for unobserved state-level factors that evolve at a constant polish office (run across eq. (3)). Models one–3 were repeated for the broader substance use treatment variable.

$$ {Y}_{st}\sim {\beta}_1\ast Eco{due north}_s+{\beta}_2\ast {Year}_t+{\beta}_3\ast {State}_s+{\beta}_4\ast {State}_s\ast {Twelvemonth}_t+\sum {\beta}_j{X}_{st}+{\epsilon}_{st} $$

(three)

To investigate whether economic weather take an asymmetric effect on the number of substance use treatment admissions during economic upturns and downturns, following the work by Mocan and Bali [26], Model four modified Model three by defining the number of substance employ admissions equally an disproportionate function of two decomposed unemployment rates during economic downturns (country unemployment rate in periods when it is higher than the prior period) and economical upturns (state unemployment rate in periods when it is lower than the prior period) (encounter eq. (4)).

$$ {Y}_{st}\sim {\beta}_1\ast Eco{n}_{down}+{\beta}_2\ast Eco{n}_{up}+{\beta}_3\ast {Year}_t+{\beta}_4\ast {State}_s+{\beta}_5\ast {State}_s\ast {Yr}_t+\sum {\beta}_j{X}_{st}+{\epsilon}_{st} $$

(four)

Econdownwards and Econupward were synthetic using state unemployment rates. Econdownward equals unemployment charge per unit in periods when it is college than the prior menses, and Econupwardly equals 0 during economic downturns. Econup equals unemployment charge per unit when information technology is lower than the prior catamenia, and Econdown equals 0 during economic upturns. The Tenst is a vector of other covariates included in the model.

$$ {Y}_{st}\sim {\beta}_1\ast {R}_{st}+{\beta}_2\ast {UR}_{st}+{\beta}_3\ast {R}_{st}\ast {UR}_{st}+{\beta}_3\ast {Year}_t+{\beta}_4\ast {State}_s+{\beta}_5\ast {State}_s\ast {Yr}_t+\sum {\beta}_j{10}_{st}+{\epsilon}_{st} $$

(5)

To test the moderation effects of economical recessions (2001, 2008–09) on the relationship between economical conditions and substance use treatment, Model v modified Model iii by adding the economic recession indicator (R) and an interaction term between the state unemployment charge per unit (UR) and economical recession indicator (R) (meet eq. (5)). All tests were two-sided and used a v% significance level. All of the analyses were performed using SAS ix.4 (SAS Found, Inc., Cary, NC) and R 3.five (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Economic condition

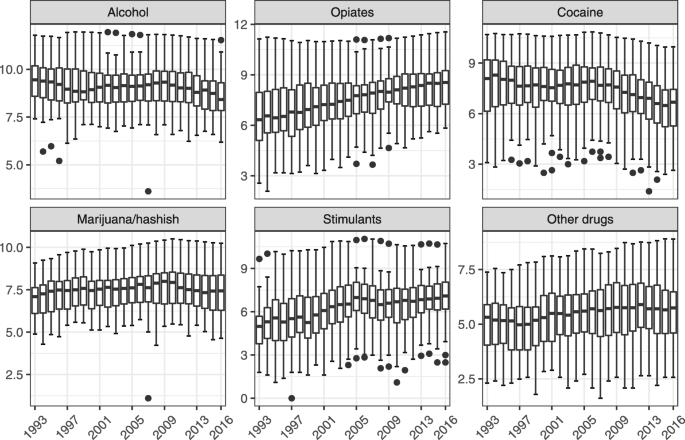

Figure 1 presents substance apply handling admissions from 1993 to 2016. The median number of state substance use treatment admissions for opiates and stimulants increased while the admissions for booze and cocaine decreased during the study period (Fig. 1).

Distribution of admissions for those aged eighteen years old and older by primary substance use from 1993 to 2016. The number of substance apply treatment admissions was presented after log transformation

Table 1 presents the clan between the state unemployment charge per unit and annual admissions to substance abuse treatment facilities. Unemployment was significantly associated with substance corruption treatment. In Model 1, a unit increase in unemployment rate was associated with a ix% [(exp (0.087)-1)*100%] increment in opioid treatment admissions (\( \hat{\beta} \) =0.087, p < .001). Similar associations were found in treatment admissions for cocaine (\( \hat{\beta} \) =0.081, p < .001), alcohol (\( \hat{\beta} \) =0.050, p < .001), marijuana (\( \chapeau{\beta} \) =0.036, p < .01), and other drugs (\( \hat{\beta} \) =0.095, p < .001). Nevertheless, states with higher unemployment rates had a lower number of treatment admissions for stimulants (\( \hat{\beta} \) = − 0.081, p < .001). In Model ii, which adjusted for state fixed effects instead of partitioning effects as in the first model, a similar clan was found between state unemployment rate and substance utilise treatment admissions, except the association was not meaning for opiates admissions (\( \hat{\beta} \) =0.002, p = 0.84). Similarly, in Model 3, after adjusting for state-year interaction in improver to Model ii covariates, unemployment rate was positively associated with booze admissions (\( \chapeau{\beta} \) =0.026, p < .001) and admissions for other drugs (\( \hat{\beta} \) =0.049, p < .001), but negatively associated with stimulants admissions (\( \hat{\beta} \) = − 0.067, p < .001). Land median household income and population were significantly associated with all substance corruption treatment admissions. Similar results were institute for the association between unemployment rate and broader estimated annual admissions.

Unemployment symmetric effects and economical recession

Table 2 shows the results of the association between state unemployment rates and almanac admissions to substance abuse handling facilities in economical downward and upward trends (Model iv). Compared to the original Model three results, unemployment rates remain negatively associated with annual admissions for stimulant treatment during economic downturns (\( \hat{\beta} \) = − 0.070, p < .001) and economic upturns (\( \hat{\beta} \) = − 0.092, p < .001). Likewise, unemployment rates were positively associated with almanac alcohol and other drug treatment admissions during economic downturns and upturns. The state unemployment rates were negatively associated with annual cocaine treatment admissions during economical downturns and economic upturns (\( \chapeau{\beta} \) = − 0.037, p < .001), only the association was not significant during economical downturns (\( \chapeau{\beta} \) = − 0.009, p = 0.35). Nosotros found that the association between state unemployment rates and annual substance abuse admissions has the same management during economic downturns and upturns. Therefore, unemployment rate appears to accept a symmetric consequence given that Econup and Econdownwardly coefficients were non statistically significantly different (except for marijuana/hashish, stimulants, cocaine).

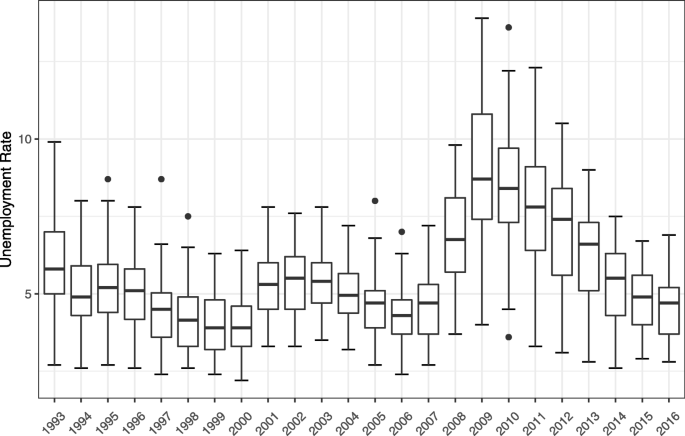

Table 3 shows the moderation analysis of how the economic recession afflicted the human relationship between country unemployment rates and substance corruption admissions (Model 5). The unemployment rate was at a peak during the ii recession periods (2001, 2008–09) (Fig. 2). Although there was a negative clan between the unemployment charge per unit and substance use admissions for stimulants (\( \hat{\beta} \) = − 0.067, p < .01) in the baseline analysis (Model 1), the interaction term showed that the negative association was weakened during the economic recession. The moderation upshot was not pregnant for other substances.

Tendency of average state unemployment rate, 1993–2016

Discussion

The present study found that the unemployment rate was significantly associated with substance corruption treatment admissions for booze, marijuana, opiates, cocaine, and other drugs. These results are in line with a prior report that found that equally county unemployment rates increased, the opioid death rate and opioid overdose emergency department visit rate both increased [27]. Additionally, prior studies reported increases in alcohol-related disorders and problematic drinking during the recession, particularly among households experiencing unemployment [9, 28]. A contempo Castilian study besides establish an increase in marijuana and cocaine use during the great recession [29]. Our results showed a negative association between unemployment rates and substance corruption admissions for stimulants; nevertheless, the relationship was altered during economic recessions. In prior enquiry, beingness unemployed or working role-time was associated with increased use of stimulants [30]. A possible caption for this discrepancy is the perception of stimulants compared to other drugs. For instance, ane report found that college students often perceive the misuse of stimulants as safe [31], and thus may not experience the need to seek treatment, peculiarly during times of economic hardship.

Our findings lend support to the idea that the self-medication model may be applicable to examining substance utilise among those experiencing economic hardship. The self-medication model of drinking suggests that alcohol is used to cope with psychological distress. Economic hardship has been associated with depression, feet, and psychological distress [28, 32, 33]. Based on our results, this theory may as well extend to illicit drug use. As a consequence of economical hardship, some may develop problems with alcohol and drugs due to self-medication, resulting in the increased rates of treatment admissions we constitute in our study. Particularly, unemployment may increment psychological distress, resulting in increasing use of and treatment admissions for marijuana, opiates, cocaine, and other drugs.

We found that the relationship between unemployment rate and almanac substance corruption admissions was mostly similar (symmetric effect) for economical downturns and upturns (with the exception of marijuana/hashish, cocaine, and stimulants). These findings suggest that, at least for some substances, the unemployment rate is consistently associated with treatment admissions regardless of the current economic climate. Our findings that substance use treatment admission is associated with unemployment indicate that during economic downturns, people may rely on substances to cope. During economic crises and times of high unemployment rates, there may exist a need for more substance use treatment facilities equally problematic substance apply increases. This study's findings propose the need to prioritize funding for substance utilize handling facilities during and after economical crises.

The present report has some limitations worth noting. Nosotros used substance treatment facility admissions as an indicator of excessive or problematic substance abuse, which merely captures a portion of substance abuse problems and may have resulted in selection bias. In addition, because of the precautions taken to ensure anonymity, some of those admitted to treatment facilities could take been double-counted if they returned for a 2d circular of treatment. Due to the nature of the current report, caution is needed when applying grouped results to the individual level (ecological fallacy). Despite its limitations, the current study expands the existing literature piece of work by using objective measures of problematic substance apply and more diverse illicit drug categories.

Conclusions

Nosotros found that unemployment was associated with substance corruption admissions for alcohol, marijuana, opiates, cocaine, and other drug use. These findings suggest that economic hardship is associated with increased substance employ and also implies that handling for substance use of sure drugs and alcohol should remain a priority fifty-fifty during economical downturns. Treatment for stimulant apply may exist the exception, every bit we found that state unemployment rates were negatively associated with treatment admissions for stimulants. Yet, the human relationship between the unemployment rate and stimulant handling admissions may be chastened by economical recession.

Availability of data and materials

Abbreviations

- TEDS:

-

Treatment Episode Data Sets

- SAMHSA:

-

Substance Abuse and Mental Wellness Services Administration

- ACS:

-

American Community Survey

- CPS ASEC:

-

Current Population Survey Almanac Social and Economic Supplement

- NCI:

-

National Cancer Institute

- DID:

-

Difference-in-deviation

References

-

Kochanek KD, Irish potato SL, Xu J, Arias Eastward. Deaths: Final Data for 2017; National Vital Statistics Reports; 2019.

-

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Results from the 2017 national survey on drug use and health: detailed tables; 2018.

-

National Institute on Drug Abuse Nationwide Trends Available online: https://world wide web.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/nationwide-trends (accessed on Oct 1, 2019).

-

Cotti C, Dunn RA, Tefft N. The not bad recession and consumer demand for alcohol: a dynamic console-information analysis of Us households. Am J Health Econ. 2015;1:297–325.

-

Chalmers J, Ritter A. The business organization cycle and drug use in Commonwealth of australia: bear witness from repeated cross-sections of individual level data. Int J Drug Policy. 2011;22:341–52.

-

Perlman FJA. Drinking in transition: trends in alcohol consumption in Russia 1994-2004. BMC Public Health. 2010;x:691.

-

Munné MI. Alcohol and the economical crisis in Argentine republic: recent findings. Habit. 2005;100:1790–9.

-

de Goeij MCM, Bruggink J-Westward, Otten F, Kunst AE. Harmful drinking later job loss: a stronger association during the mail service-2008 economic crunch? Int J Public Health. 2017;62:563–72.

-

Gili M, Roca G, Basu S, McKee M, Stuckler D. The mental health risks of economical crisis in Spain: evidence from primary care centres, 2006 and 2010. Eur J Pub Wellness. 2013;23:103–viii.

-

Compton WM, Gfroerer J, Conway KP, Finger MS. Unemployment and substance outcomes in the United States 2002-2010. Drug Booze Depend. 2014;142:350–3.

-

Arkes J. Does the economy bear on teenage substance utilise? Health Econ. 2007;16(1):19–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.1132.

-

Arkes J. Recessions and the participation of youth in the selling and use of illicit drugs. Int J Drug Policy. 2011;22:335–40.

-

Weston BW, Krishnaswami S, Gray MT, Coly G, Kotchen JM, Grim CE, Kotchen TA. Cocaine use in inner city african american inquiry volunteers. J Addict Med. 2009;three:83–8.

-

Colell Eastward, Sánchez-Niubò A, Delclos GL, Benavides FG, Domingo-Salvany A. Economical crunch and changes in drug utilize in the Spanish economically agile population. Addiction. 2015;110:1129–37.

-

Carpenter CS, McClellan CB, Rees DI. Economic conditions, illicit drug use, and substance use disorders in the U.s.a.. J Wellness Econ. 2017;52:63–73.

-

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Handling Episode Data Set: Admissions Available online: https://world wide web.datafiles.samhsa.gov/written report-series/treatment-episode-data-set-admissions-teds-nid13518 (accessed on Sep thirty, 2019).

-

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index (CPI) Databases Available online: https://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm (accessed on Oct ane, 2019).

-

US Census Bureau Historical Income Tables: Households Available online: https://www.demography.gov/data/tables/fourth dimension-series/demo/income-poverty/historical-income-households.html (accessed on October 1, 2019).

-

US Bureau of Labor Statistics Local Area Unemployment Statistics Bachelor online: https://world wide web.bls.gov/LAU/ (accessed on Oct ane, 2019).

-

ProCon 33 Legal Medical Marijuana States and DC - Medical Marijuana - ProCon.org Bachelor online: https://medicalmarijuana.procon.org/view.resources.php?resourceID=000881 (accessed on Oct one, 2019).

-

Tax Policy Center State Alcohol Excise Taxes Available online: https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/statistics/land-alcohol-excise-taxes (accessed on Oct 1, 2019).

-

US Census Bureau Wellness Insurance Historical Tables - HIC Series Available online: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/wellness-insurance/historical-series/hic.html (accessed on Oct i, 2019).

-

National Cancer Institute Download U.Due south. Population Data - 1969-2017 Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/popdata/download.html (accessed on Oct ane, 2019).

-

The National Agency of Economic Research United states of america Business organisation Bike Expansions and Contractions Available online: http://world wide web.nber.org/cycles/ (accessed on Oct 1, 2019).

-

Angrist, J.D.; Pischke, J.-S. Mostly harmless econometrics: an empiricist'south companion; Princeton university printing, 2008; ISBN 1-4008-2982-8.

-

Mocan HN, Bali TG. Asymmetric Crime Cycles. Rev Econ Stat. 2010;92:899–911.

-

Hollingsworth A, Ruhm CJ, Simon K. Macroeconomic conditions and opioid corruption. J Health Econ. 2017;56:222–33.

-

Brown E, Wehby GL. Economic conditions and drug and opioid overdose deaths. Med Care Res Rev. 2019;76:462–77.

-

Bassols NM, Castello JV. Furnishings of the great recession on drugs consumption in Spain. Econ Hum Biol. 2016;22:103–xvi.

-

Perlmutter AS, Conner SC, Savone M, Kim JH, Segura LE, Martins SS. Is employment status in adults over 25 years old associated with nonmedical prescription opioid and stimulant use? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52:291–8.

-

Weyandt LL, Janusis Thousand, Wilson KG, Verdi G, Paquin G, Lopes J, Varejao Chiliad, Dussault C. Nonmedical Prescription Stimulant Utilize Among a Sample of College Students: Relationship With Psychological Variables; 2009.

-

Williams DT, Cheadle JE. Economic hardship, parents' depression, and human relationship distress among couples with young children. Soc Ment Health. 2016;6:73–89.

-

Mirowsky J, Ross CE. Historic period and the effect of economical hardship on low. J Health Soc Behav. 2001;42:132–50.

Acknowledgments

Lauren Manzione provided editorial assistance.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

S.A. conceptualized, designed the report, and supervised the writing and analyses. L.S. conducted the data analysis. F. Q and Chiliad. W critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors canonical the last manuscript as submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they accept no competing interests.

Boosted information

Publisher'south Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open up Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in whatever medium or format, equally long as you lot give advisable credit to the original author(south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other tertiary political party material in this article are included in the commodity's Artistic Eatables licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the fabric. If textile is non included in the commodity'southward Creative Eatables licence and your intended utilise is not permitted past statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you volition demand to obtain permission direct from the copyright holder. To view a re-create of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Artistic Eatables Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/nothing/1.0/) applies to the data fabricated available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and Permissions

Almost this article

Cite this article

Azagba, South., Shan, L., Qeadan, F. et al. Unemployment rate, opioids misuse and other substance abuse: quasi-experimental evidence from treatment admissions data. BMC Psychiatry 21, 22 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02981-7

-

Received:

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1186/s12888-020-02981-7

Keywords

- Substance abuse handling

- Treatment admissions

- Opioids

- Economic conditions; unemployment rate

Source: https://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12888-020-02981-7

0 Response to "Unemployment and Substance Use a Review of the Literature (1990-2010)"

Post a Comment